Categories Pastry Chef Articles

How to temper chocolate according to Ramon Morató

The book Chocolate by Ramon Morató, Best Chocolate Book in the World (Gourmand World Cookbook Awards), now in its fifth edition, is one of the great monographic books on cocoa and chocolate for the professional sector.

Published by Grupo Vilbo and available in a bilingual version (English & Spanish) in our Books For Chefs online bookstore, it contains more than 200 recipes as well as studies on mousses and truffles, general characteristics for preparing fillings, among many other technical aspects.

Below we share one of the book’s chapters, dedicated to the pre-crystallization or tempering of chocolate.

Why do we temper chocolate?

If we melt chocolate or chocolate couverture to add it into any confection such as a mousse, a base for an ice cream, a sauce to be served with a dessert, etc., we recommend to follow the advice included in the section on pastry-making regarding the addition of chocolate to other ingredients. This way, any problems about texture and aspect will be avoided.

On the other hand, if the aim is to melt the chocolate in order to transform it with the intention that it regains its original consistency and gloss after being prepared (e.g. in order to coat a bonbon, mold some Easter eggs, spray an artistic confection with chocolate or decorate), the process of tempering or pre-crystallization of chocolate has to be carried out irremediably.

We define ‘tempering’ as a process through which the chocolate mass goes from a liquid state (after being melted) to a stable solid state.

As seen in the section on cocoa products, a dark chocolate couverture (for example) consists of sugar, cocoa paste, cocoa butter, vanilla and lecithin. We can confirm that it is solid when at room temperature, but it melts when heated and then becomes liquid. It is important to point out that when the chocolate couverture is heated, the only ingredient undergoing a physical transformation is cocoa butter.

When chocolate is melted, we obtain a typical dispersion. Those ingredients not containing fat are scattered in a continuous fat phase. Basically, the cocoa solids and the sugar are distributed in the cocoa butter.

We can therefore state that cocoa butter and the fatty elements or oils which accompany it (in the case of milk and white chocolate couvertures or giandujas and pralines) are mainly responsible for the final liquid or solid state of chocolate.

Pre-crystallization is therefore linked only to the fatty part of the mass. Let us see a clear example below:

If we melt cocoa butter at approximately 50ºC and we keep it in a plastic container with no movement at all, we will observe that a solid part and a liquid one are obtained at 20ºC for a few hours. We can see big cocoa butter crystals in the solid part. However, if any mechanical movement had been applied to it during the cooling process, we would obtain small fat crystals and the cocoa butter would look like a homogeneous mass.

If consulted the end of this section, we can verify that one of the aims of the pre-crystallization of chocolate is to obtain an appropriate contraction. This makes the unmolding easier if the chocolate is to be used for bonbon molding.

If leaving the hot cocoa butter in the container with no movement or stirring at all, there is no contraction but expansion. There have been some cases in which the cocoa butter even broke the container.

The aim of a good tempering process is to pre-crystallize the chocolate mass until it reaches an appropriate crystallization stage. We have to create a solid fatty part within the chocolate mass we are working with, disperse with the rest of ingredients; for this reason, this process is called ‘pre-crystallization’.

Studies show that when chocolate is properly tempered, between 1 and 2% of solid cocoa butter in the form of fat micro-crystals is obtained, which will serve to force the rest of the fat to solidify after undergoing the required process (coating, molding, etc.).

For example: Let us imagine we have two couvertures at a temperature of 30ºC at our disposal. We cool one of them on a granite worktop with a constant stirring and we heat the other one in a container and then leave it to cool down to 30ºC as well but without stirring it.

Both couvertures have the same temperature, but they do not contain either the same type or the same amount of solid fat crystals. This will obviously lead to different results regarding gloss, texture and contraction in the couverture.

This therefore shows that the temperature is not so important but the creation of solid fat crystals within chocolate.

In conclusion, when we heat a mass like chocolate, the fat it contains melts. We then need to cool it again in order to allow a part of this fat to become solid again. Only by doing this we can guarantee a proper crystallization after using this chocolate (i.e. after coating bonbons, decorating a product, etc.).

See the chart on SFC (Solid Fat Content) included in the section on fats. Now that we know that we need to create fat crystals in our mass, let us see below what kind of crystals there are.

The main crystal forms and their respective temperature range are as follows:

- Gamma up to 18ºC

- Alpha 18 to 24ºC

- Beta’’ 24 to 28ºC

- Beta’ 28 to 33ºC

- Beta 33 to 35ºC

The crystals which are stable at room temperature are the beta-type, for this reason the process is aimed at obtaining this type of crystal. It is quite logical that, as most our products are kept at 20-22ºC, we search for forms with the highest possible stability range. Furthermore, we have to bear in mind that cocoa butter crystallizes in varied different forms. Polymorphism is defined as the property a substance has to be able to crystallize in different crystal forms and dimensions. In the case of cocoa butter, it is particularly important.

Some of these forms are the main cause of the appearance of unstable crystals, some others create stable crystals at serving temperature. Only the stable form crystals allow us to obtain resulting characteristics like the ones stated below. For this reason, out of these different crystal forms, only the beta’ and beta crystals produce stable solids. I wish the concept of the pre-crystallization of chocolate is clear. After reading this part, and as a conclusion, I invite you to take an iced drink in your hands:

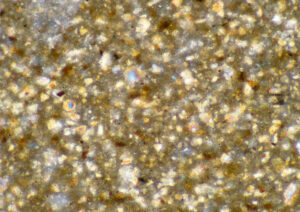

As shown in the picture, there is a mass full of ice crystals suspended within a liquid aqueous part. Thanks to this ice, the iced drink will freeze in an uniform and even way in a few minutes if placed into the freezer, but the ice crystals will disappear if left at room temperature.

In the case of tempered chocolate couverture, we have a mass full of small crystals of solid fat which will enable a regular and quick cooling. If on the contrary we heat the mass again, these will also disappear.

Tempering process

To proceed with the tempering of chocolate, we have three main principles at our disposal:

- Tempering of the chocolate on a cold point: on a granite table, in an inverted Baine Marie, and in a tempering machine.

- Tempering of the chocolate by seeding stable crystals: by adding drops.

- Tempering by maintaining part of the already existing crystals: in a stove or maintaner, and in a microwave.

Tempering of the chocolate on a cold point

Tempering of the chocolate by seeding stable crystals

Tempering by maintaining part of the already existing crystals

In Chocolate, you will find details about these three principles from four points: melting the chocolate, creation and seeding of stable crystals, visual and temperature check, and test of the final result.

Average temperatures of tempering and crystallization of the couverture

We have to bear in mind that the temperatures shown below are merely indicative. After acquiring experience, one can already tell if the couverture is properly pre-crystallized just by noticing how its viscosity changes and how shiny its mass becomes.

- Dark chocolate couverture 30-32ºC

- Milk chocolate couverture 29-30ºC

- White chocolate couverture 28-29ºC

On the crystallization of the couverture

Once the tempering process is finished, if the mass is too thick and/or contains solid couverture lumps, this is due to an excessive crystallization of couverture. At this stage, the couverture has to be heated by adding in a small amount of hot couverture or using a microwave oven in order to increase its temperature between 0.5 and 1ºC.

Regarding small amounts of couverture (such as 2 or 4 kilos), we have proved that for every 10 seconds in a microwave oven on high power the temperature is increased in approximately 1ºC. We should work within the limits of temperature for each type of couverture. This way, the product will have a longer preservation time in perfect conditions. While it cools down, it is advisable to apply heat on the sides of the container with the help of a heat gun, thus avoiding any piece of solid couverture that could make the rest of the couverture crystallize excessively. One of the most common problems is that the couverture thickens too much after a while working it, which makes it nearly impossible to continue working it.

If this couverture starts to crystallize, it cannot release the heat from the solidification because it is in a hot container (such as a chocolate warmer). Heat is then accumulated within its own mass, thus leading to a thickening effect (which is contradictory, as heat should logically keep the couverture in a liquid state). This phenomenon is known as ‘vaselinization’, which is also very common when using wheel machines.

In order to lengthen the usable time of this couverture, the temperature has to be increased by from 1 to 2ºC by adding some hot couverture or heating it with the microwave oven, etc.